Chapter 3 : The Attack on Memory

He was so alive. Tangibly alive. Everyone-else-was-dead-by-comparison alive. It dawned on me how every form of vitality I had known before was merely the manifold masks of desperation.

Soundtrack (it sounds the best by earphones playing at higher volume)

*

*

*

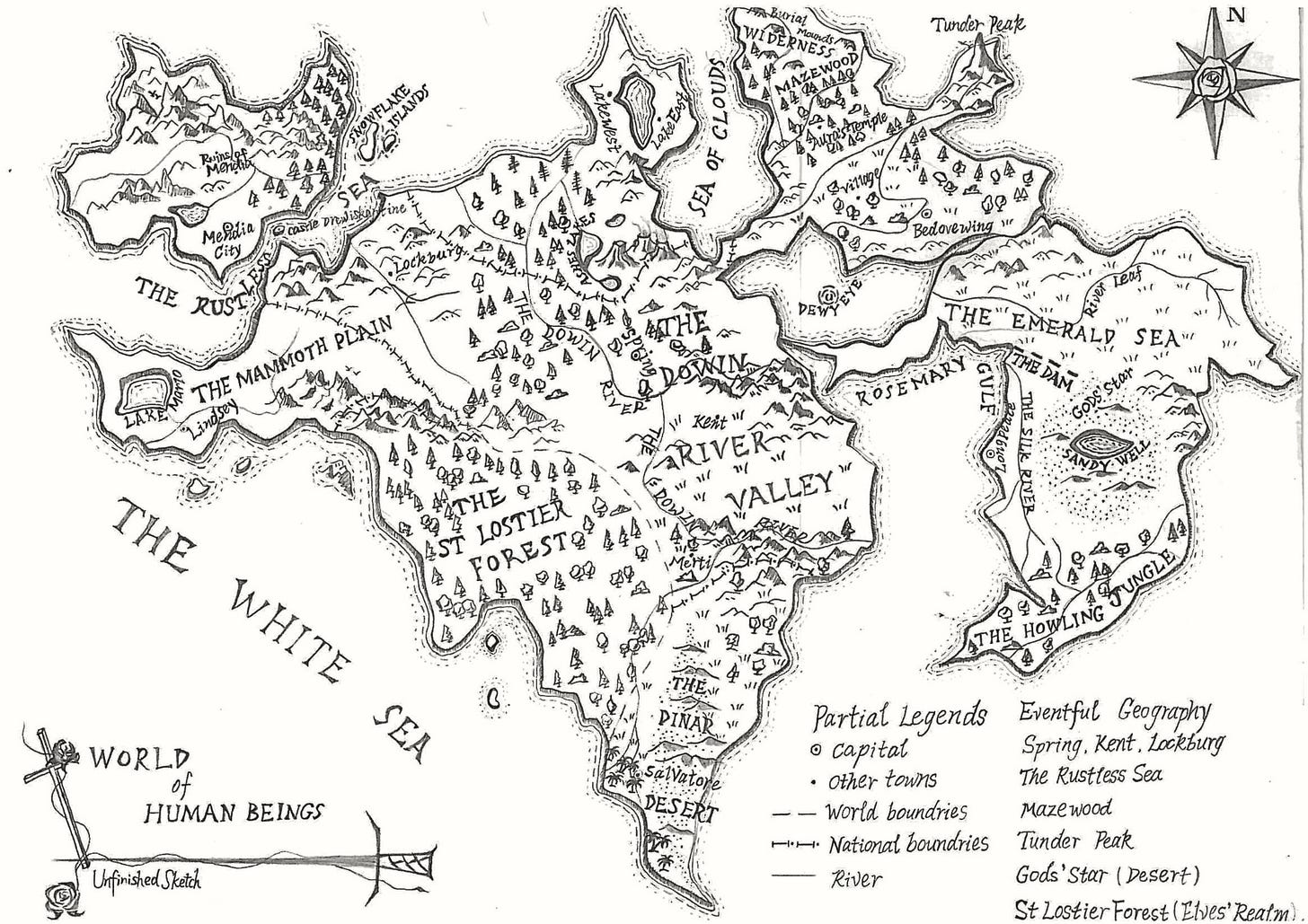

Places mentioned:

Sanlostier:

The forbidden forest that seems to be ruled by a certain subspecies of Elves.

Mount Wind Bell:

A mountain that stands by the border between two parallel worlds—the Elves and Men—and two contiguous human kingdoms—Linsaidea and Tyrannoson.

Linsaidea:

One of the three kingdoms on the Central Continent, northwest of Tyrannoson, across a narrow sea, the Rustless Sea, to Mandia. A nomadic, rather savage people that tame mammoths.

Dinar:

One of the three kingdoms on the Central Continent, south of Tyrannoson, a desert nation.

Mandia:

An island nation, northwest of the Central Continent, cut off by the Rustles Sea. It was conquered by Tyrannoson three years ago when the narrative begins.

Tyrannoson:

One of the three kingdoms on the Central Continent, ruled by the Valrino family.

Spring

The capital city of Tyrannoson.

Dowin River Valley:

Mertie, a small rural village and Ivan’s hometown, falls within the scope of this valley, a fertile land with abundant waters.

*

*

Creatures (that can speak and have names) mentioned:

Philemon

The son of the Lord of Sanlostier

Phisens

One of the seven gods, who seems to be the god of Elves

Leopoldo Valrino

The King of Tyrannoson, and the 6th monarch of the Valrino family.

*

*

*

3

The Attack on Memory

"I should've killed him with my own hands," Philemon bit out his words.

"He would die with or without your revenge."

"You saw him die."

His father didn't answer.

"Your vision is making you passive."

"Philemon."

I almost heard Philemon's heavy breath slowly subside, and eventually, he managed to say, "Forgive me."

Before his father responded, he added, "If you always act upon your vision, how come you allowed it to happen?"

“It’s not that simple.”

“You said the truth is always simple.”

“But it’s not always easy.”

A gust of wind blew through the woods, and many blossoms fell off and shattered. Then they melted, seeping into the soil like morning dew. Yet more kept falling, shattering, and melting.

“She had visions too. She made the choice.”

“To be—killed?”

“Yes.”

Yes.

While I was still staggering over my hearing—not the content but the clarity—the branches parted. Immediately, my wonder shifted from his words to his presence.

Standing under the grandiose trees, with only his reflection in the gleaming "well," taller and broader compared to Philemon, his bare feet paced beneath a garment of lilac tints. Silvery, cascading hair, strands of it floating as he turned around and fixed his eyes on me for a glimpse. Then he waved his broad sleeves that shimmered like the surface of water, and in a breeze, leaped up into the tree.

"Take him away," he spoke from the tree.

"But it's unusual that a white deer would lead him into the forest," Philemon said, looking up.

"And the white deer?" the voice from above asked.

"He was killed by one of the corrupted Blood Elves we arrested."

"Then he is responsible for the deer's death."

"No, Father. My point is, he was supposed to be dead before he could come this far. No Man has ever managed to do that."

Philemon's defense backfired for unknown reasons.

"Guards!" his father ordered. At once, a dozen elves sprang up from nowhere and surrounded me, aiming arrows at my head from all directions, even from the trees.

"Take him to the dungeon. No one is to see him or release him without my order!"

"Philemon! Philemon!" I yelled at the branch wall as the elves pushed me away.

The rope around my wrists tightened, as the end was still in Philemon's hands. The guards hesitated, waiting for a new order. Silence grew and crept over the branch wall. Seconds later, the other end of the rope slipped through the branches and fell to the ground. I was then escorted to the Elves' dungeon.

* * *

I passed by where they annihilated the corrupted Blood Elves; many of them were being burned in a stone house that resembled a kiln, separated by creeks on barren ground with no greens. I saw the three Elves, including Mere, who were with us earlier standing outside the stone house. A few screams erupted and lasted for less than a minute before fading. They glanced at me blankly, and I was about to yell out "Philemon" as that was the only word they understood, but they looked away, as if they had never known me.

I turned to the Elves who were escorting me. “Please, let me speak to your prince. We had a deal.”

They didn’t respond.

“Philemon! Philemon, your prince!”

“Hey! I know your language! Isn’t that something?”

I was only making noises to them. I wished I could speak the Elvish tongue so they would be impressed and find me useful. They took me along a winding path up to the mountain—Mount Wind Bell—on the border of Sanlostier and the two kingdoms of Man. It was an extremely long distance from the Dowin River Valley to Mount Wind Bell. The valley was in the southeast of Tyrannoson, while the mountain was to its northwest.

In case the location was still unclear, let me explain further: it would take me three days and two nights to ride from the Valley to Spring, which was only half the distance from the Valley to the Mountain. But it took us barely an hour on foot to walk through Sanlostier.

We walked up the stone steps to the mountain's waist. The north side of the mountain belonged to Man, while the south belonged to the Elves.

By Man, I meant the people of Linsaidea, who occupied the Plain of Mammoths. Across the entire Central Continent, they were the closest to barbarians. Their knights rode mammoths, and their kings or queens sat in a box on top of a mammoth. They believed in primal, armless fights and spear hunting; they worshiped fire and weapons—yet they were the neighbors of Elves who abhorred both.

Strangely enough, Linsaidea and Tyrannoson had never been at war, and they even supplied us with food and allowed transportation through their territory during the Mandia War. Such generosity from Linsaidea wasn't unconditional; they requested a connection through marriage. When the Linsaidea king's youngest daughter turned 15, we would send a prince to be her husband in Linsaidea. It was considered a great insult—even hostage-taking—to marry a prince off to a foreign land, but for some reason, King Leopoldo, whom I was supposed to serve, agreed.

The princess just turned fifteen this past winter. I knew this because my father had prepared his wedding gift for the selected prince: a bottle of elixir that could detoxify any man-made poison.

Any man-made poison.

He was not poisoned by anything man-made!

I sprang up and started storming around. I couldn't just die here. I must get out. I had to find out the truth.

The upper south side of Mount Wind Bell was carved with thousands of cells for prisoners like me. The cells were open but high up in the clouds, with no way to escape except suicide. I could hear screams and moans carried by the wind, vultures and other raptors flocking and striking any cells on this side of the mountain that reeked of death or frailty. I paced back and forth to show vitality. After a few hours, I would be starving, and in a few days, I would be dying with no strength left to fight off a swarm of vultures with my bare hands.

I staggered over Philemon's rope. It was still around my wrist and had become so tight that it almost cut off my blood flow. I needed to send signals to Philemon—but could he even free me from this dungeon? There was no real entry or exit. A giant creature had lifted me and dropped me in my cell. It was essentially a bird, about three men's height, with two strong talons.

Three sunrises later, the giant bird flew up to the dungeon again, carrying something in its talons—Man or Elf, I couldn’t tell. I sprang up, despite my weakness, and shouted with all my might in the Elvish language that I’d been practicing non-stop, “Philemon! Prince! Lord! I know him!”

The bird slid away in a blast of wind.

Its disappearance began the hardest thing I’d been through—from dawn to dusk, in despair, in hunger and thirst, in helplessness, with nothing to cling to—no expectations, no distractions—just a raw collision with time, rubbing against it back and forth, just, waiting.

I lay on the ground, holding onto three comforts to keep myself together—together, yes; I now believed that life was not one-dimensional and that life was only in its abundance when all dimensions worked together.

The first was, being Man, I would die, sooner or later. I would not linger in torment.

Second, with a gleam of hope, I must tell Philemon that annihilation might be how to end everything, to kill something twice—once for life, once for being—it was by no means the worst punishment. There must be somewhere that drowned and burned, kept you dead yet without an end—for mercy was in all endings.

Third, the Lord of Sanlostier, the one who sent me here. In awe of that majestic tree he stood under, that glimmering well containing his reflection, the sound of his voice, I had peace, a trembling peace. This awe overpowered all emotions, such as grudges.

Part of me wanted to get out so I could investigate the death of my father, but hanging around eternal beings had affected me. He had already died—that one thing I wanted to change I could not. What good, then, would any add-ons such as investigation and revenge do?

Besides, it made me anxious thinking about living under the nose of the most dangerous family on this continent.

My lips were parched, and a blast of wind brought me a chill as the sun was setting. My eyes glazed over, and I saw the giant bird flying straight toward me. I was so depleted that it almost felt like a chore to get up and leave. So I remained lying there like a stranded fish, bracing for worse. Was it taking me away? No, its talons were holding something, probably a new prisoner.

However, the bird dropped the object into my cell. I turned and sat up too quickly, and dizziness struck me. Through my wobbling, darkened vision, I perceived something golden, but I couldn’t tell if it was sun rays or—

“You can speak our language. Are you not Man?”

I could have burst into tears if not for dehydration. Philemon bowed and leaned closer to examine me, frowning.

He spoke to me in the Elvish tongue for the first time and looked bewildered. I was afraid he would abandon me for fooling him, so I struggled to stand up as I stammered to explain in the common tongue, “Not really, I… I only understand a little.”

He cocked his head, dubious and intrigued, and continued to speak in Elvish, "You can't just understand a little. You either speak or you do not."

"I probably learned it on the way." I responded in human language—he insisted on Elvish, and just like that, we went back and forth.

"You can't learn Elvish," he said, and he lowered his eyes, as if doubting his own knowledge.

"I speak many tongues—I mean, many human languages and dialects. I learned them." I was trying to help him get over this so he could help me get out of here.

He didn't respond, while a persistent "No, you can't learn Elvish" was all over his face.

The sun was almost below the horizon, and the sky was a crystalline purple. I noticed that Philemon had a pair of sapphire eyes with intricate labyrinths in them, delineated and brightened by clear whites of eyes, just like everything about him—defined and divine, like a tree of jade outside his father's chamber and the leaves clinking in the breeze and the blossoms kept falling and shattering, making melodies that overflowed with life.

He was so alive. Tangibly alive. Everyone-I-knew-was-dead-by-comparison alive.

“The bird will not take anyone down from the dungeon unless my father orders it to do so,” he said. “So, our only chance is to climb down the cliff using tools.”

He signaled to the rope around my wrists.

My knees went weak just hearing his plan. “How long will it take to climb down this mountain?”

“Three days for you.”

“I’m starving.”

He lowered his eyes, thinking.

“Do you have birds like that to carry me?”

“You’re too heavy for her.”

As the purple of the sky consolidated into dark blue, an idea came to me: instead of climbing down, we could climb over the mountain to the other side.

“I can’t,” Philemon rejected immediately. “That’s beyond the forest.”

“No one would notice an Elf crouching on a huge mountain in the clouds and in the dark.”

“No, I can’t. Just like you’re not supposed to be here, I can’t cross the border.”

“But here I am.” I shrugged, tracing a flicker of hesitation in his eyes. “Maybe your god Phisens wants me to be here, and he wants you to cross the border with me.”

“Phisens was dead.”

“Clearly he didn’t. You elves are still keeping his law.”

“He died for that very reason.” Philemon narrowed his eyes, warning me to stop blaspheming.

I shook my head. Worshiping a dead god who died to keep his laws alive—Elves must be so bored with living forever.

“I will help you get down the mountain,” Philemon said as he went ahead of me. “Then you must go down by yourself and never come back.”

“That’s cruel.”

He stopped and turned a bit of his face. “Why?”

“I’m joking,” I said, raising my hands.

He turned more of his face, frowning. Even though it was dim, I could tell he was upset.

“Fine, I’ll shut up.”

We began to climb over Mount Wind Bell. Philemon hopped onto the rocks above me with incredible balance and then pulled me up with the rope around my torso whenever necessary. Twice I almost fell when the rocks I stepped on broke off from the cliff, but Philemon held the rope firmly, allowing me to dangle and then clutch back onto the cliff. I thought he might be dragged down by my weight, but he wasn’t. I marveled at an Elf’s physical prowess: feathery, dexterous, fast, precise, and incredibly strong. During my whining, Philemon started talking again in the Elvish tongue, trying to gauge how much I knew about it. With each exchange, he corrected me—probably because he just couldn’t bear how I ruined their ethereal language.

Finally, we reached the peak and stopped to catch our breath—by “our,” I mostly mean myself. I sat there, panting and feeling my muscles twitch, while Philemon stood, gazing into the darkness with his eyes wide open.

“How far can your eyes see?” I asked out of curiosity.

“As far as my view is not blocked.”

I looked at him as he surveyed the plateau below, seeing through the gossamer clouds floating past, the dry, yellowed fields, and the scattered bonfires. He noticed figures moving around and creatures whose existence he hadn’t known, performing actions he couldn’t understand. I was almost proud of the expression on his face.

A thought flared across my mind just now: if he would go down the mountain with me, I would not go to Spring. I would be wanted by the King, be in exile, be a nomad in the wilderness—as long as I could stick around Philemon. It dawned on me how every form of vitality I had known before was merely desperation, which was lost on Philemon, who had eternal life.

He found some fruit and shared it with me, warning me not to eat too much after I had swallowed six or seven pieces that tasted like peaches. A full stomach recovered me from my madness and—if I were honest—selfishness. It was at this point that our coming farewell, which would be forever, started to embitter me.

Soon after we began our much slower descent in the breaking dawn, he stopped behind me, looking lost.

“What’s going on?” I turned around, walking back toward him.

“I wasn’t supposed to cross the border.”

“But you did! We’ve come so far, and now you’re going home?” I uttered with difficulty, as my heart pulsated in my tight throat. I didn’t know what to feel or what I was expecting.

“I wasn’t supposed to be able to.” He was completely absorbed in confusion, touching the air around him and turning back and forth as if testing something invisible to me.

“This should be the border, but it didn’t stop me—no Elves can break through the border. God Phisens built it, just like no human can break into Sanlostier—”

“That’s not true,” I spread my arms, trying to ease him while I was not at ease.

“You were led by a white deer,” he stressed that point again. “The gateway opens when there’s an invitation from the animals of either world. There must be a reason you are here, and my father must have seen that too. He wouldn’t have left you to die in that dungeon, even if I hadn’t come, especially if he knew you spoke our language.”

“Then why did you come to save me?”

He didn’t answer.

“Because I’m a Man,” I said intentionally in Elvish.

He tried to say something but ended up looking away.

“You’re meant to leave the forest, or the border would have stopped you by now.”

This time, he glanced at me, pretentiously alert. “My father was right. Men are deceitful.”

“There are many good men,” I insisted. “Your parents just happened to encounter the worst kind. And maybe I am no ordinary man. I crossed the border and speak your language. Just like you, you—”

I realized, just like me, that he was full of mysteries which he didn’t even know himself. Starting from this point, I lost my self-consciousness about what language we were speaking and let go of my tongue. Fluent Elvish flowed out of my mouth like it was innate.

“You want to hunt those perverted Blood Elves, don’t you?”

He gave me a glare, knowing that I had overheard his conversation with his father.

“If you don’t, what will they do?”

“They will prey on Man.”

“How could you let that happen?”

“I have no responsibility for them,” he said as he turned around.

“You just crossed the border and can speak our language,” I raised my voice, no longer knowing who I truly was while speaking Elvish out loud. “Do you think that means nothing?”

He paused walking but didn’t turn to me.

“I speak the human tongue because someone taught me.”

“Who? Your father?”

“I don’t remember.”

“Then how did you know it was taught—”

He hopped up the hill without speaking a word, disappearing behind the invisible border.

* * *

Things, like shimmers, came toward me palely. Where I was and what time it was, I did not know. How I got here, I had forgotten.

After seeing the letter of appointment from my King, a Linsaidea aristocrat residing at the border between the three realms—Sanlostier, Tyrannoson, and Linsaidea—was surprised at how I had come this far in a day.

His surprise surprised me. I was certain that I had seen three sunrises in the Elves’ dungeon alone, not to mention the night climbing over Mount Wind Bell and that long night walking through Sanlostier.

I lied, saying that I happened to be in the vicinity. He didn’t pursue that further and treated me well, preparing feasts and the best guest room, even providing prostitutes—they freaked me out. I grabbed a lamb shank, a string of grapes, and a few loaves, fled to my room, panting with my back against it. I slid down to the ground and ate all of them in the darkness. The next morning, he gave me a delicate silver case about the size of two palms as he sent me off to Tyrannoson.

“Please give this to your king,” he said.

“What is this?” It wasn’t much heavier beyond the weight of the case. I doubted it was any precious stone.

“It’s my gift.”

“I can’t just bring a box to the king. You have to show me what is in it.”

He hesitated briefly and gestured for me to open it.

It looked like a shell, gold in color, with a luster of fine pearls, but the texture was much harder, with no scratch marks or signs of abrasion. I raised it to my eyes, and the sun half-penetrated it, tinting its outer surface—the rough side—iridescent. The inner surface was soft and smooth, with the color of skin as if it were alive, and there were micropores around the margin.

I turned to my Linsaidea host and noticed that he had been looking at me all this time, as if I should know what this was. When he saw that I seemed even more confused, he eased up a bit.

“A slave girl of mine discovered this by the river, the one where they do laundry at the lower stream. She was trying to hide it, but my steward brought it to me,” he said, studying me. “You are the new Maester of Tyrannoson. What do you say?”

“A shell,” I flipped it back and forth, “or a scale?”

“That’s what I’m concerned about,” he said. “Fish with a scale of this size have never been heard of in that river. You came from the Dowin River; have you seen any fish with that kind of scale?”

“I don’t think so. But I’m no fisherman.”

“Not even Dowin River has fish that large,” he said.

“It could come from the ocean.”

He shook his head with a smile. “You know how far we are from the ocean. That thin river does not come from or run to the ocean.”

I didn’t have much time to unwrap clues one by one with him, so I asked rather bluntly, “What does this have to do with my King?”

“I’m afraid this is not from any ordinary creature.” He leaned in and stressed in a whisper, “It could be sorcery.”

He stared at me as he stepped back.

I nodded, just wanting to get rid of him, whose motives had been so ambiguous from the day he welcomed me to his home. Wake up, you old freak; the time of “purging” had long gone. Our King is not going to remember your “favor.”

The Tyrannoson army received me at the border, put me in a wagon, and dispatched two grooms to send me to Spring.

All this time, from the Linsaidea man’s mansion to the bumpy road trip in a comfy wagon, I felt like I was waking up in a tomb. Everything and everyone appeared dead to me. I appeared dead to me.

Something had shifted in the air. Something thick and heavy shrouded the realm of Man, and even sunlight could not disperse that dimness, that oppression. Even sunlight shone upon the earth as a punishment for the sun. I had been having a headache since the night I escaped the feast of gourmet food and naked women. I had never had any contact of any form with women. Now those foreign women, bolder and thicker than my own people, flashed back to me—their curves, their scents, their touches, and their giggling. Bored and lethargic in the wagon, I let go and slipped into the sensualities until I saw the perverted Blood Elves overshadowing their breasts in my hands. Right after that, Philemon jumped down from the tree and rescued me from this perversion that moved but had no life.

I was jolted back to reality, deprived. Had I never known life, I would never have perceived death all around me.

I had been trying to—yes, with effort, though without reasons—remember Sanlostier; a conscious effort I made, clinging to the memory as if clinging to life. Yet day after day, meal after meal, nightmare after nightmare, in this relentless headache that came out of nowhere, that memory slipped through my fingers, despite how tightly I gripped onto it.

Finally, after four days of non-stop travel, I rode into Spring, and immediately, my fatigue was lifted by a surge of alertness: there was no plague in the capital city. The guards who had been sent to escort me from Mertie had lied to me. But why? According to human time, I was only one day delayed, and the guards were not even here yet. I doubted they would trespass the forest to search for me. More than likely, they were searching around the forest.

The King neither condemned me for being late nor celebrated me as the new Maester. He was as indifferent as if I’d been living in the castle and simply came to wish him a good day.

And he couldn’t have been farther from how I had assumed him to be.

Really engaging story and what a wonderful job you've done of bringing these characters to life.

Please don't take this the wrong way.

To make things more realistic, I would suggest using a single term in the elvish language to describe the "corrupted blood elves".

After all,we use the term "scum" to refer to people we see as reprehensible. The elves would probably use a term that connotes revulsion or serves as a cautionary tale.Also, calling them "corrupted blood elves" seems a bit too long.

Secondly,why not give the elvish language a name?,Much like we would call chinese languages,Cantonese or Mandarin.

I think it would make this more realistic and interesting.

I thought there were one or two errors as well, knowing how much work it takes to edit,it's understandable.

The chapter was interesting and your tale holds promise,I look forward to how you weave it.